Wireless intrusions

For many years now, ISPs deliver a router including an access point. And Wi-fi is integrated into more devices than just homes or company LANs. Every mobile phone or tablet has Wi-fi support nowadays. The VoIP infrastructure of some supermarket announcements are routed over Wi-fi. Advertising panels in buses, railways and at stations, and even surveillance cameras often use Wi-fi as a transport medium.

Wireless is cheap, individually deployable and popular and therefore often built into the most unexpected places, blind to the associated massive security risks. In this evolving industry with ever more devices connected to wireless networks, understanding wireless security threats and countermeasures is critical.

Common attack vectors wireless

Many of the attacks on wireless networks involve eavesdropping, the process of capturing the traffic, making a copy of it so that it can be read if it is not encrypted (or cracking the encryption key if it is encrypted).

An attacker can perform a man-in-the-middle (MiTM) attack (on-path attack), intercept the traffic, and then modify the traffic before forwarding it on to the wireless access point.

Data corruption attack methods involve altering or corrupting the data so that it is not readable by the destination system.

A relay attack is the capturing of a wireless signal and sending it somewhere else. This type of attack is commonly used to compromise vehicle key fobs. Using a special transmitter, an adversary can relay the signal from the key fob of a car to a teammate who receives the relayed signal to open the door of the car.

Spoofing refers to altering a source address, whether that is the source MAC address or source IP address of a packet, or the source email address of an email message. It is a common phenomenon in wireless attacks for bypassing MAC filtering on a wireless access point.

Common Wi-Fi attack scenarios

Sniff Wi-Fi traffic, and gain access:

Connect to unencrypted network

Connect to encrypted wireless network

Break WEP encryption by FMS attack, Korek’s chop-chop, PTW attack, or a Caffe Latte attack

Break WPA encryption by Beck-Tews attack, Halvorsen-Haugen attack, or Brute force PMK

ARP/MAC spoofing (MitM)

For a Denial of Service attack, Jam radio signal, flood with broadcast of frames, or use a disassociation/deauthentication attack

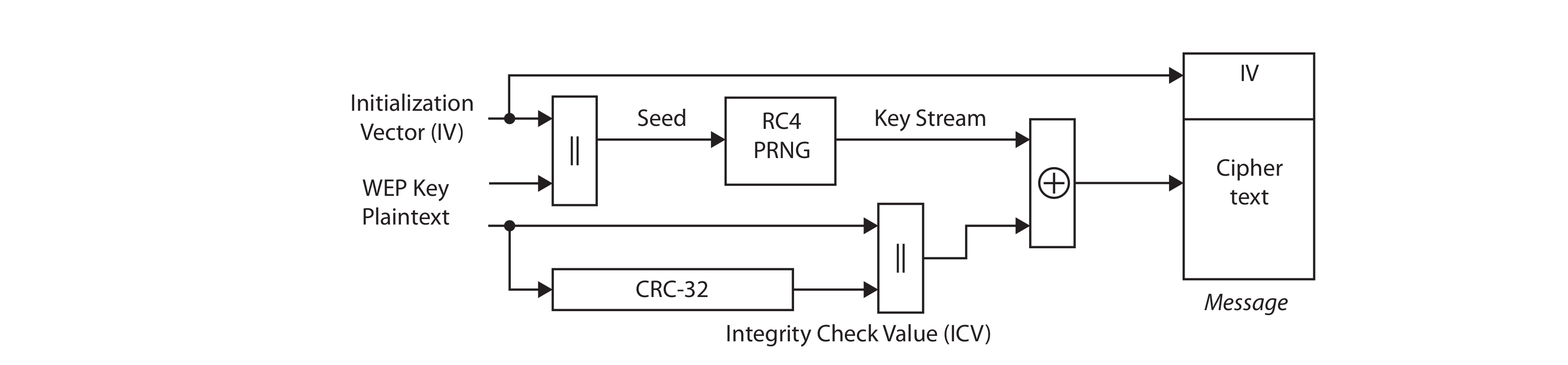

WEP

WEP was the standard before WPA. The WEP encryption process uses the RC4 stream cipher. RC4 is a symmetric key cipher used to expand a short key into an infinite pseudo-random keystream.

A number of flaws in the WEP algorithm seriously undermine the security claims of the system. Possible attacks are:

Passive attacks to decrypt traffic based on statistical analysis.

Active attack to inject new traffic from unauthorised mobile stations, based on known plaintext.

Active attacks to decrypt traffic, based on tricking the access point.

Dictionary-building attack that, after analysis of about a day’s worth of traffic, allows real-time automated decryption of all traffic.

Key reuse in the encryption stream (24-bit IV) makes it vulnerable to cracking, as well as to fragmentation and replay attacks. aireplay-ng can be used to generate IV samples and aircrack-ng to decipher the secret key. You can also use wifite to conduct attacks against WEP.

WPA and WPA2

WPA was introduced as an interim replacement for WEP and did not require consumers to replace hardware to support the new security measure. Instead, most vendors released software/firmware updates that could be installed on existing devices. There are multiple flavors of WPA based on the 802.11i wireless security standard: WPA, WPA2, and WPA3.

WPA increased from 63-bit and 128-bit encryption in WEP to 256-bit encryption technology. WPA implemented the Temporal Key Integrity Protocol (TKIP) after WEP encryption was broken. TKIP is symmetric encryption that still uses the same WEP programming and RC4 encryption algorithm, but it encrypts each data packet with a stronger and unique encryption key. It also includes some additional security algorithms made up of a cryptographic message integrity check, IV sequence mechanism that includes hashing, a rekeying mechanism to ensure key generation after 10,000 packets, and to increase cryptographic strength, it includes a per-packet key-mixing function.

These were designed to add protection against social engineering, replay and injection attacks, weak-key attacks, and forgery attempts.

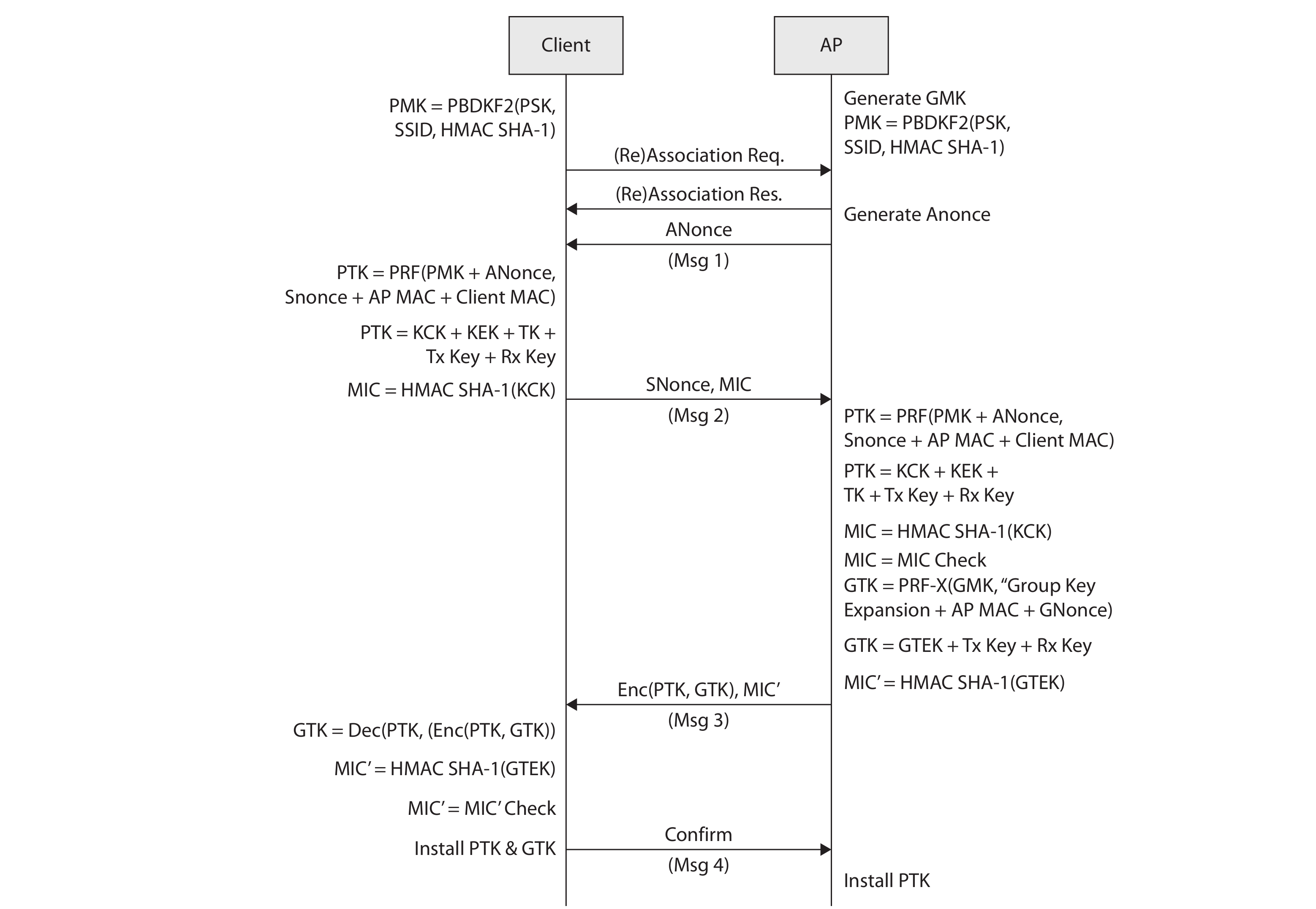

WPA2 introduced the use of the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) instead of TKIP. After 2006, all new devices bearing the Wi-Fi trademark required mandatory WPA2 certification. WPA and WPA2 use a four-way handshake to establish connection.

WPA3

Like WPA2, WPA3 uses AES and a four-way handshake. Its main difference with WPA2 is that it is designed for perfect-forward secrecy. This means that the encryption key changes such that its compromise will not result in a breach of data encrypted before that compromise took place. IOW, a privacy feature that prevents older data from being compromised by a later attack.

Additionally, WPA3 uses Simultaneous Authentication of Equals (SAE) in an attempt to solve WPA and WPA2’s vulnerability to dictionary attacks. SAE is a type of key exchange also referred to as Dragonfly.

WPA3 is weak to downgrade attacks and timing attacks. The Dragonblood vulnerabilities target the Dragonfly key exchange.

Scanning and sniffing

In contrast to a Wi-fi scanner a Wi-fi sniffer passively reads the network traffic and in the best case evaluates also data frames beside beacon frames to extract information like SSID, channel and client IPs/MACs.

Scanning

Sniffing

Probe-Request sniffing

Sniffing for hidden SSID

Probe-Request

If an operating system is sending out a probe request for every network it was connected to, an adversary can not only conclude where its owner has been, but may even get the WEP key (if that is still used) when it tries to connect to these networks and only receives a probe response(it then reveals its WEP key).

Deauthentication attacks

A deauthentication attack occurs when a hacker forces the access point to disconnect a wireless client from the access point. The client will automatically reconnect to the access point. Before deauthenticating, the adversary will start capturing wireless traffic to capture the authentication traffic (the handshake) when the client reconnects to the access point. The captured traffic can help crack the encryption key.

Start capturing traffic

Deautheticate clients

Crack keys

Example deauthentication attack

aireplay-ng -0 1 -a <MAC address of access point> -c <MAC address of target> wlan0mon

Following is a list of the parameters:

-0tells Aireplay-ng to perform a deauthentication attack (you can also use –deauth).1specifies the number of deauthentication messages to send. You can use0for unlimited.-ais the MAC of the access point to send the message to.-cis the MAC address of the client to deauthenticate. If -c is not used, all clients are deauthenticated by the access point.wlan0monis the interface to use.

Cracking WEP

Verify wireless NIC

Discover networks with Airodump-ng

Capture traffic with Airodump-ng

Associate with access point and replay traffic

Crack the WEP key

Verify wireless NIC

View and document wireless adapter:

# airmon-ng

Create an interface that runs in monitor mode:

# airmon-ng start wlan0

Write down interface name (something like wlan0mon)

Discover networks with Airodump-ng

Display a list of wireless networks (Ctrl+C to stop):

# airodump-ng wlan0mon

The BSSID is the MAC address of the wireless access point that has been detected.

PWR is the power level of the access point. The lower the number, the better the signal strength to that access point. This is a way to determine how close you are to the access point (unless the administrator changed the power level).

CH is the channel the access point is operating on, such as 1, 6, or 11.

ENC is encryption type used, such as WEP, WPA, or WPA2.

CIPHER is the cipher being used, such as TKIP, CCMP, or WEP.

ESSID is the name of the wireless network.

At the bottom of the output are the MAC addresses of the access points and the clients (stations) connected to those access points.

Capture traffic with Airodump-ng

In a new terminal window, capture traffic for a specific wireless network:

# airodump-ng -c <channelnumber> -w <filename> --bssid <MAC address of access point> wlan0mon

Associate with access point and replay traffic

To crack the WEP encryption, a large number of packets (approximately 100.000 packets) are needed.

Associate with the access point first:

# aireplay-ng --fakeauth 0 -a <bssid of the access point> wlan0mon

Replay ARP traffic:

# aireplay-ng --arpreplay -b <bssid of the access point> wlan0mon

Crack the WEP key

Specify the .cap file by the filename created earlier, but add a dash and a 01 because it is the first time. Just leave it running to keep trying until it cracks the WEP password:

# aircrack-ng <filename.cap>

Once the password is cracked, a “KEY FOUND!” appears at the bottom of the output followed by the encryption key in hex format within square brackets. Copy this value without the square brackets and remove the colons (:) before entering the key to connect to the wireless network.

WPS pin attack

Wi-Fi Protected Setup, or WPS, is a wireless standard protocol used by WPA and WPA2 protected networks that helps autoconfigure wireless clients with the wireless encryption password so that they do not need to input the password. WPS is commonly found in consumer appliances and may use in-band methods, such as using a personal identification number (PIN) during setup or pushing a button to initiate the network discovery process, or out-of-band methods such as near field communication (NFC), where proximity initiates the connection.

Many wireless access points and routers have a WPS button that you can press to connect a wireless client to the network via the WPS protocol. After clicking the button, you then go to the client device (typically a laptop or a smartphone) and choose to connect to the wireless network. You are automatically connected without needing to input the wireless password because the wireless access point or router has communicated the configuration information to the client for you.

As part of the WPS standard, wireless access points and routers that support WPS must have an 8-digit pin configured. This can be viewed on the wireless access point. When connecting the client to the wireless network, the pin can be supplied instead of the wireless password.

The problem with WPS is that the WPS–enabled router is vulnerable to having the WPS cracked due to the fact that the pin was originally designed as two 4-pin blocks. It is much quicker to crack two 4-pin blocks than it is one 8-pin block.

Verify wireless NIC

Scan for potential WPS vulnerable networks

Brute-force the WPS pin

Verify wireless NIC

View and document wireless adapter:

# airmon-ng

Create an interface that runs in monitor mode:

# airmon-ng start wlan0

Write down interface name (something like wlan0mon)

Scan for potential WPS vulnerable networks

Wash is included in the Reaver package:

# wash -i wlan0mon

In the list are the BSSIDs (MAC address) of the access points, the channel, and the ESSID (network name), and whether the WPS protocol is locked (in other words, whether it is protected from WPS brute-force attacks). Look for a no.

Brute-force the WPS pin

Using Reaver:

# reaver -c <channel> -b <bssid> -i <interface> -vv

Cracking WPA/WPA2 keys

Verify wireless NIC

Discover networks with Airodump-ng

Perform deauthentication attack

Crack the WPA/WPA2 key

Verify wireless NIC

View and document wireless adapter:

# airmon-ng

Create an interface that runs in monitor mode:

# airmon-ng start wlan0

Write down interface name (something like wlan0mon)

Discover networks with Airodump-ng

Display a list of wireless networks (Ctrl+C to stop):

# airodump-ng wlan0mon

The BSSID is the MAC address of the wireless access point that has been detected.

PWR is the power level of the access point. The lower the number, the better the signal strength to that access point. This is a way to determine how close you are to the access point (unless the administrator changed the power level).

CH is the channel the access point is operating on, such as 1, 6, or 11.

ENC is encryption type used, such as WEP, WPA, or WPA2.

CIPHER is the cipher being used, such as TKIP, CCMP, or WEP.

ESSID is the name of the wireless network.

At the bottom of the output are the MAC addresses of the access points and the clients (stations) connected to those access points.

Perform deauthentication attack

In a new terminal window, do a deauthentication attack on all clients connected::

# aireplay-ng --deauth 0 -a <bssid of access point> wlan0mon

This allows the airodump-ng command running in the other terminal to capture the handshake traffic when re-authentication happens. After a few minutes, switch back to the terminal whereairodump-ng is running, to view the WPA handshake information that was captured (top of the screen).

Switch back to the aireplay-ng terminal to stop the deauthentication traffic (Ctrl+C).

Crack the WPA/WPA2 key

Crack the WPA/WPA2 encryption key using a brute-force method with a password list file:

# aircrack-ng <filename.cap> -w <wordlist_file>

Once the password is cracked, a “KEY FOUND!” appears at the bottom of the output followed by the encryption key. Copy this value and enter the key to connect to the wireless network.

Use Ctrl+C to stop any remaining commands in terminals.

Using Wifite

In a terminal, type the

wifitecommand to automate a wireless attack. The network card is placed in monitor mode, and then it scans for wireless networks. The wireless networks with the stronger signals are placed at the top.After two minutes of scanning for networks, press Ctrl+C to stop.

Type the number of the wireless network you would like to attack (assess). Wifite will attempt to crack the WPS pin and then continue by using tools such as

aircrack-ngin order to attempt to crack the WPA2 encryption key.

Use the wifite -help command to get a list of wifite possible switches. For example, if you just want to do the WPS cracking with Wifite, use the -wps switch.

Dragonblood attack

WPA3 implements SAE (Dragonfly key exchange). The Extensible Authentication Protocol-Password (EAP-PWD) authentication method, which is used in some intranets, also uses Dragonfly handshakes and may be vulnerable to some of the same attacks.

It is vulnerable to multiple types of attacks, even despite the implementation of additional security measures. WPA3 connections can be tricked into downgrading to a weaker protocol (such as WPA2), or choose a weak security group using a rogue AP and forged messages, or discern information about the password based on timing of responses to commit frames.

Rogue access points

Evil twin attack

Karma attack

Captive portal

Evil twin attack

An evil twin attack occurs when an adversary sets up a fake access point that impersonates a real access point for network users to access.

It is not always easy for a user to determine which is the correct Wi-Fi network and which is the fake. Both networks can have the same SSID and the same (or expected) encryption protocol and can be placed close to the targeted user(s) so that its signal strength is high, and it is put at the top of the client’s list of APs.

Using any kind of encryption protocol will require that the user knows the password, which may not be feasible. In which case, the evil twin is set to operate in open mode.

Karma attack

Some devices, especially those running older operating systems, will send out active probe requests for known Wi-Fi networks rather than waiting passively for an AP to send a beacon frame. An adversary listening for such a request can respond with their own rogue AP information and prompt the client to connect.

In a karma attack, the adversary does not need to broadcast a spoofed SSID to entice users and potentially raise suspicion.

Captive portal

A captive portal is the term for the web page that appears that asks users for their login credentials when connecting to a wireless network, most likely a guest wireless network, such as wireless networks found at airports or cafés. A captive portal attack occurs when the adversary sets up a captive portal for the evil twin network that is used to prompt the user for the user’s password. Unsuspecting users may enter their passwords, not knowing they are connected to the fake Wi-Fi network. Once the adversary has the password, no time needs to be spent on capturing and cracking wireless traffic.

Downgrade and SSL strip

Both Karma and Evil Twin can be used in combination with an on-path attack which intercepts all traffic coming from the wireless client.

The connection with the server uses normal HTTPS. The connection with the client uses either a weaker version of SSL (downgrade attack, more easily cracked), or no encryption at all, using cleartext HTTP (SSL strip attack) between the hack machine and the client.

Both cases depend on the user permitting a connection to a website with an untrusted certificate. The certificate used in a downgrade attack is a self-signed certificate from the adversary machine.